|

Today is December 31, 2013, and it doesn't matter.

I woke up about 30 minutes ago, checked my email, my text messages, began plotting my outfit for a party I'm going to tonight and realized that tomorrow is the first of the year. And I just didn't care. I haven't spent the last two weeks waiting with anxiety for this day to mark the beginning of a major shift in my life. I don't have a single special goal, or a big big dream for a whole new _______. I do not plan to exercise more. I do not plan to eat more kale. I smiled when I realized how proud I was of my goal-less New Year's Eve. I remember when I used to look forward to New Year's Eve because I felt the final night of each year held the magical potential to usher in a whole new life, a whole new me. Every single NYE I thought about how much weight I was going to lose in the new year. I would develop a diet plan and an exercise regimen, and then obviously I would eat every imaginable delicious thing because this was going to be the last time I had anything like that in my mouth for a very long time. This is a ritual that many people participate in, so maybe it seems like it's completely normal. But it's not. I don't think wishing you were a totally different person for several days (weeks? months?) a year is normal. I think this whole obsession with goals and aspirations on NYE is a tradition worth eradicating. Why? Because this tradition is based in capitalism, patriarchy, and fatphobia that's why! Even though not having NYE goals seems like the easier option, I realize that it's actually a huge deal not to give into a pervasive cultural ritual. So, I won't tell you to just throw those out the window if you have them. But I will ask you to look over your goals and see which ones are based in the belief that you're not enough right now, just as you are. And I will ask you to cross those off the list. I have to go now and get some delicious coffee and a cheesy biscuit thing because not having goals is hard work and stuff. But the last thing I want to tell you is that no matter what your plans are for tonight or tomorrow you are hot and great and magical and enough. xo, Virgie This blog continues to be free through community support. Yay! Want to support me in my continued efforts to generate fat positive content online? Donate now <3 Recently a Facebook group asked its followers what they thought of a Plus Size Barbie.

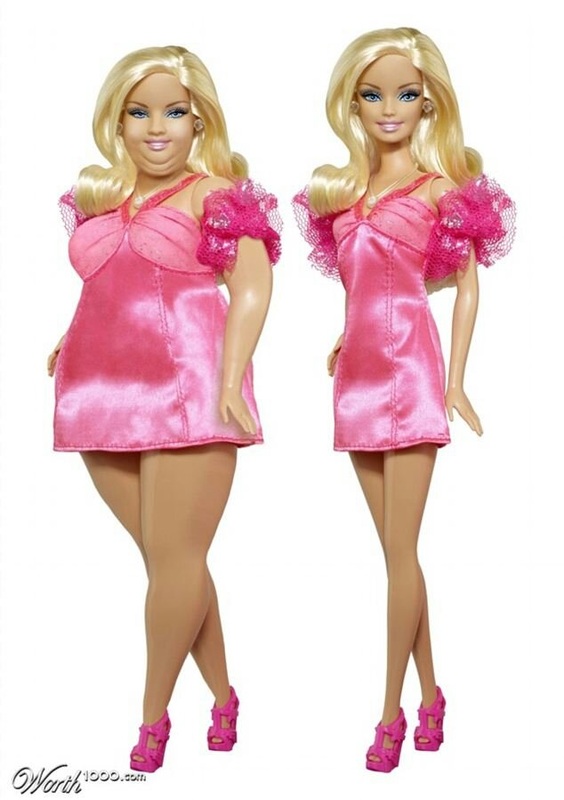

Though the mock-up (see above) got the thumbs up from over 40,000 people, several thousand others left comments disparaging the look or "message" a fat Barbie might send. Barbie was invented in 1959 and has since become a touchstone of American culture and feminist discourse, with many arguing that the doll in its current form promotes an impossible ideal. My relationship to Barbie in childhood was characterized by desire, admiration and the implicit knowledge that she was more than a doll with great boobs. One year for my birthday I was given a Barbie knock-off with bigger feet and a longer face. I rejected that faux Barbie because she was sacrilegious in my mind. Real Barbie was dainty. Real Barbie was perfect : white, thin, with great outfits and a cute boyfriend who loved her. Most of my Barbie memories involve bath time (some of the only alone time I got as a little girl) and working out confusing stuff (like romance and boys) through role plays with Barbie, her crew and Ken. I knew she represented something bigger, something I was supposed to want, something I did want. The significance of dolls in developmental psychology has been exemplified by the 1940s Clark studies in which Black children were asked to choose which of two dolls - one black, one white - they prefered and overwhelmingly chose the white doll. This study was conducted again in 2006 with similar results. Dolls seem to play the role of confirming - among other things - cultural ideals, which can be internalized and potentially affect long-term ideas of self worth and belonging. Barbie functions to showcase and teach children a kind of ideal American femininity. This ideal has been called into question as recently as last year. Nikki Minaj's recent comandeering of the Barbie name and logo indicates the potential for Barbie to be critiqued, re-envisioned, and reclaimed. Likewise, Plus Size Barbie - and the anxiety she has drummed up online - serves to remind us that we are talking about much more than a plastic toy. Make no mistake that Plus Size Barbie debate represents much more than a battle over the proportions of a doll but what American ideals of femininity are and will be. This blog continues to be free through community support. Yay! Want to support me in my continued efforts to generate fat positive content online? Donate now <3 I was recently skyped into Al Jazeera's The Stream to discuss weight discrimination and fat stigma alongside The Fat Chick, Jeanette DePatie, and Glen Gaesser, author of Big Fat Lies (which I'm currently reading). If you didn't get a chance to watch our discussion live you can watch it online now with this link:

https://ajam.app.box.com/s/nnfg1cq8ybdz0sam2ivk You may have heard that "Fit Mom" Maria Kang attacked the recent Curvy Girl Lingerie campaign that took a stand against fat shaming online by showcasing selfies of "normal women" with "lumps, bumps, scars and stretch marks." When Facebook responded to her post by banning Kang temporarily for hate speech she told Yahoo! that she felt like she'd been "sent to the principal's office" and characterized the backlash as an over reaction to "this weight issue." From a November 25 Yahoo! Shine article: “We’ve become so sensitive to this weight issue that people who speak out against it are vilified... It’s so backwards to me.” In this statement, Kang attempts to position herself as a victim of those fighting to end size-based discrimination - characterizing legitimate concern and critique as an issue of sensitivity rather than one of social justice. Furthermore, Kang uses the language of victimization to position her views as a minority opinion when in fact there is compelling evidence that the bigotry she voiced is far more in line with cultural norms than the message that the Curvy Girl campaign was attempting to convey. Negative body image - and some of its attendant disorders - is a pervasive cultural concern. Proactive campaigns - like that of Curvy Girl Lingerie - that feature countervailing images and messages are integral to changing the discussion about the significance of body diversity and creating space for women to heal from the pervasive thincentric ideal presented by mass media. Though Kang's statement seems to dismiss the fight against fat discrimination, it is worth re-centering this discussion as one firmly based in civil rights and ending discrimination. As a fat activist, I am not engaged in a "weight issue," and in my opinion neither is Curvy Girl owner, Chrystal Bougon. I am part of a movement seeking to eradicate social and institutional fatphobia. I am part of a movement that advocates for the end of discrimination based on size. I am part of a movement that promotes the belief that women don't need to have an "excuse" if their bodies do not adhere to social expectations of fitness. One of the issues I feel none of the articles on this debacle have addressed is the role that gender, race and class play in Maria Kang's messaging.

When I look at Maria Kang I see a woman of color. When I read what she has to say I see ideas that are deeply impacted by the stifling pressures of a fatphobic, sexist and racist culture. Her "What's Your Excuse?" image truly asks the viewer to justify not only her body but her very existence. In this question lies a challenge, and moreso, an accusation. To me, Kang's question echos longstanding US narratives (like bootstrapping) that simplistically reduce things like employment and class ascendency to "hard work." Fitness ideals fall perfectly in line with the rigid individualism that characterizes so many of the impossible standards to which Americans are subject. I see her dogged defense of an ideology that does not actually benefit or humanize her (or really anyone) as the internalization of rhetoric that has long been used against people of color, women and working class people. I absolutely do not seek to absolve Maria Kang of autonomy or responsibility, but do wonder about her (and others') investment in this type of self-defeating ideology. The attention and overwhelmingly supportive response that the Curvy Girl campaign has received indicates the growing fortitude of a movement to end size discrimination. This work is more than a bunch of sensitive fat girls sending the Maria Kangs of the world to the principal's office. The simple truth is this: I'm not fighting for the right to lord my amazing jiggly thighs over others in a jpeg. I'm not fighting for the right to give people boners. I'm not fighting for the right to be a hot mom. I'm fighting for a life that feels like it belongs to me. I'm fighting for all the people who have been taught that hating themselves is normal. I'm fighting for every fat girl who perpetually has the word sorry half-formed on her lips. I'm fighting for liberation. |

Virgie Tovar

Virgie Tovar, MA is one of the nation's leading experts and lecturers on fat discrimination and body image. She is the founder of Babecamp (a 4 week online course focused on helping people break up with diet culture) and the editor of Hot & Heavy: Fierce Fat Girls on Life, Love and Fashion (Seal Press, 2012). She writes about the intersections of size, identity, sexuality and politics. See more updates on Facebook. Archives

April 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed